The History

of Visual

Communication

The Late Gothic and the Early Rennaisance

The Late Gothic

The time of the Incunabula books and the subsequent developments in printing with moveable type correspond to the historic period we call Late Gothic, transforming itself into the early Renaissance in Europe.

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Southern and Central Europe. In the late 14th century, the sophisticated court style of International Gothic developed, which continued to evolve until the late 15th century. In many areas, especially Germany, Late Gothic art continued well into the 16th century, before being subsumed into Renaissance art. Primary media in the Gothic period included sculpture, panel painting, stained glass, fresco and illuminated manuscripts.

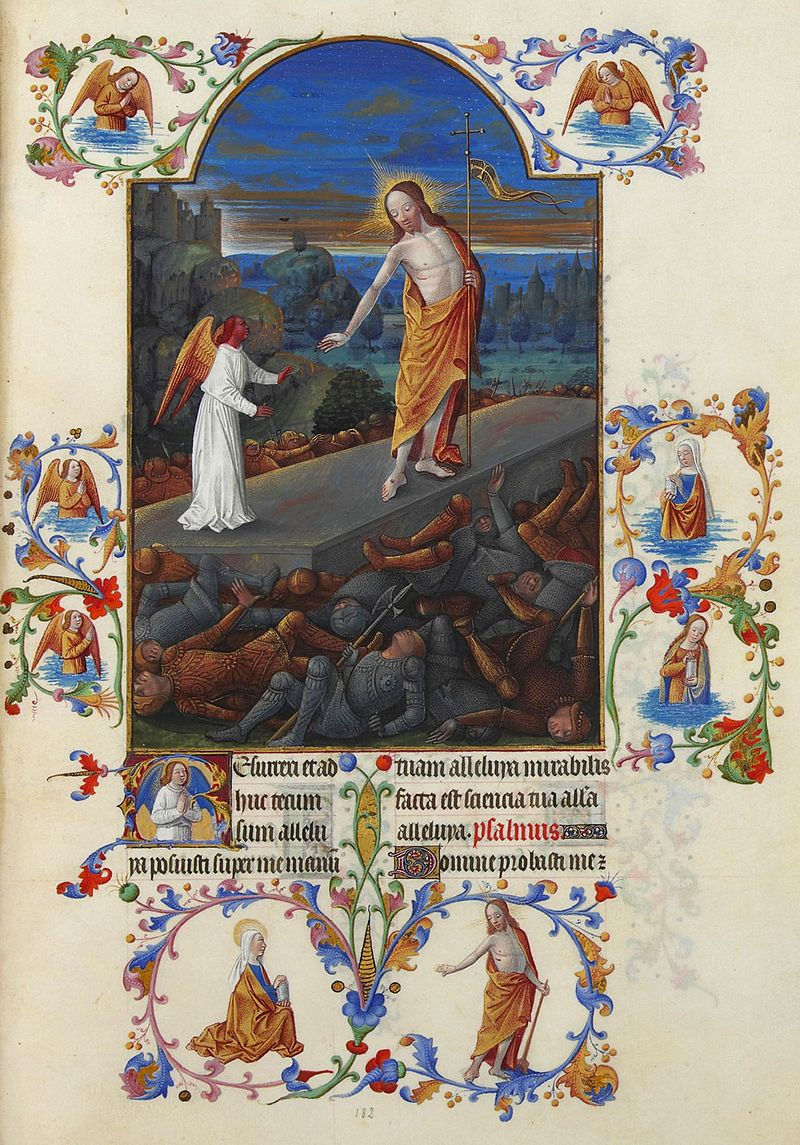

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is the most famous and possibly the best surviving example of French Gothic manuscript illumination, showing the late International Gothic phase of the style. It is a book of hours: a collection of prayers to be said at the canonical hours. It was created between 1412 and 1416 for the extravagant royal bibliophile and patron John, Duke of Berry, by the Limbourg brothers.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |

Northern Europe

Two Flemish Painters: The Master of Flémalle and Jan Van Eyck

Robert Campin (1375 – 1444), also known as the Master of Flémalle, is considered the first great master of Early Netherlandish painting. Campin did not sign his paintings, therefore none can be securely connected with him. Thus the corpus of work is attached to the unidentified "Master of Flémalle." His early work shows the influence of the International Gothic painters but displays a more realistic observation which he achieved through innovations in the use of oil paints. Campin taught both Rogier van der Weyden and Jacques Daret and was a contemporary of Jan van Eyck.

Jan van Eyck (1390 – 1441) was one of the most significant Northern Renaissance artists of the 15th century. He was employed as a court painter to Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, until 1429 before moving to Bruges, where he lived until his death. He was highly regarded by Philip, and undertook a number of diplomatic visits abroad, including to Lisbon in 1428 to explore the possibility of a marriage contract between the duke and Isabella of Portugal.

Van Eyck painted both secular and religious subject matter, including altarpieces, single panel religious figures and commissioned portraits. He was well paid by Philip, who sought that the painter was secure financially and had artistic freedom and could paint "whenever he pleased". Van Eyck's work comes from the International Gothic style, but he soon eclipsed it, in part through a greater emphasis on naturalism and realism. Van Eyck was highly influential and his techniques and style were adopted and refined by many of the Early Netherlandish painters.

A particularly beautiful manifestation of Late Gothic/early Renaissance art came about in early Netherlandish painting which is sometimes also referred to as the school of Flemish primitives who were active in the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands during the 15th- and 16th-century Northern Renaissance; especially in the flourishing cities of Bruges, Ghent, Tournai and Brussels. Their work follows the International Gothic style and begins approximately with Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck in the early 1420s. Early Netherlandish painting coincides with the Early and High Italian Renaissance but is seen as an independent artistic culture, separate from the Renaissance humanism that characterized developments in Italy.

The major Netherlandish painters include Campin, van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Dieric Bouts, Petrus Christus, Hans Memling, Hugo van der Goes and Hieronymus Bosch. These artists made significant advances in natural representation and illusionism, and their work typically features complex iconography. Their subjects are usually religious scenes or small portraits, with narrative painting or mythological subjects being relatively rare. Landscape is often richly described but relegated as a background detail before the early 16th century. The painted works are generally oil on panel, either as single works or more complex portable or fixed altarpieces in the form of diptychs, triptychs or polyptychs.

I should also say here that I have chosen to start this section with samples of early Netherlandish paintings despite the fact that the developments in typography and printing techniques did not primarily occur in the Netherlands, but elsewhere. I am doing so since it seems to me that these paintings show us the zeitgeist of Northern Europe, which is the milieu in which the likes of Gutenberg and Duerer worked, are illustrated by them in a most wonderful way. These paintings give us a very good feel of what life in Northern Europe during the times of the development of the movable type printing press must have been like.

Bosch's pessimistic and fantastical style cast a wide influence on northern art of the 16th century, with Pieter Bruegel the Elder being his best-known follower. His paintings have been difficult to translate from a modern point of view; attempts to associate instances of modern sexual imagery with fringe sects or the occult have largely failed. Today he is seen as a hugely individualistic painter with deep insight into humanity's desires and deepest fears.

Hieronymus Bosch (1450 – 1516) was an early Netherlandish painter. His work is known for its fantastic imagery, detailed landscapes, and illustrations of religious concepts and narratives. Within his lifetime his work was collected in the Netherlands, Austria, and Spain, and widely copied, especially his macabre and nightmarish depictions of hell.

The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things is a painting attributed to a follower of Hieronymus Bosch, completed around 1500 or later. Four small circles, detailing the four last things — "Death of the Sinner", "Judgment", "Hell" and "Glory" — surround a larger circle in which the seven deadly sins are depicted: wrath at the bottom, then (proceeding clockwise) envy, greed, gluttony, sloth, extravagance (later replaced with lust), and pride, using scenes from life rather than allegorical representations of the sins.

Bruegel's earthy, unsentimental and vivid depiction of the rituals of village life—including agriculture, hunts, meals, festivals, dances, and games—are unique windows on a vanished folk culture, and a prime source of iconographic evidence about both physical and social aspects of 16th century life. Using abundant spirit and comic power, he created some of the very early images of acute social protest in art history. Examples include paintings such as The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (a satire of the conflicts of the Protestant Reformation). On his deathbed, he reportedly ordered his wife to burn the most subversive of his drawings to protect his family from political persecution resulting from conflicts between the Catholic Church and the Protestant Reformation.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525 – 1569) was a Netherlandish Renaissance painter known for his landscapes and peasant scenes. From 1559, he dropped the 'h' from his name and signed his paintings as Bruegel. Bruegel specialized in genre paintings populated by peasants, often with a landscape element, but he also painted religious works. Making the life and manners of peasants the main focus of a work was rare in painting in Bruegel's time, and he was a pioneer of the genre painting.

Altar Paintings and Tryptychs

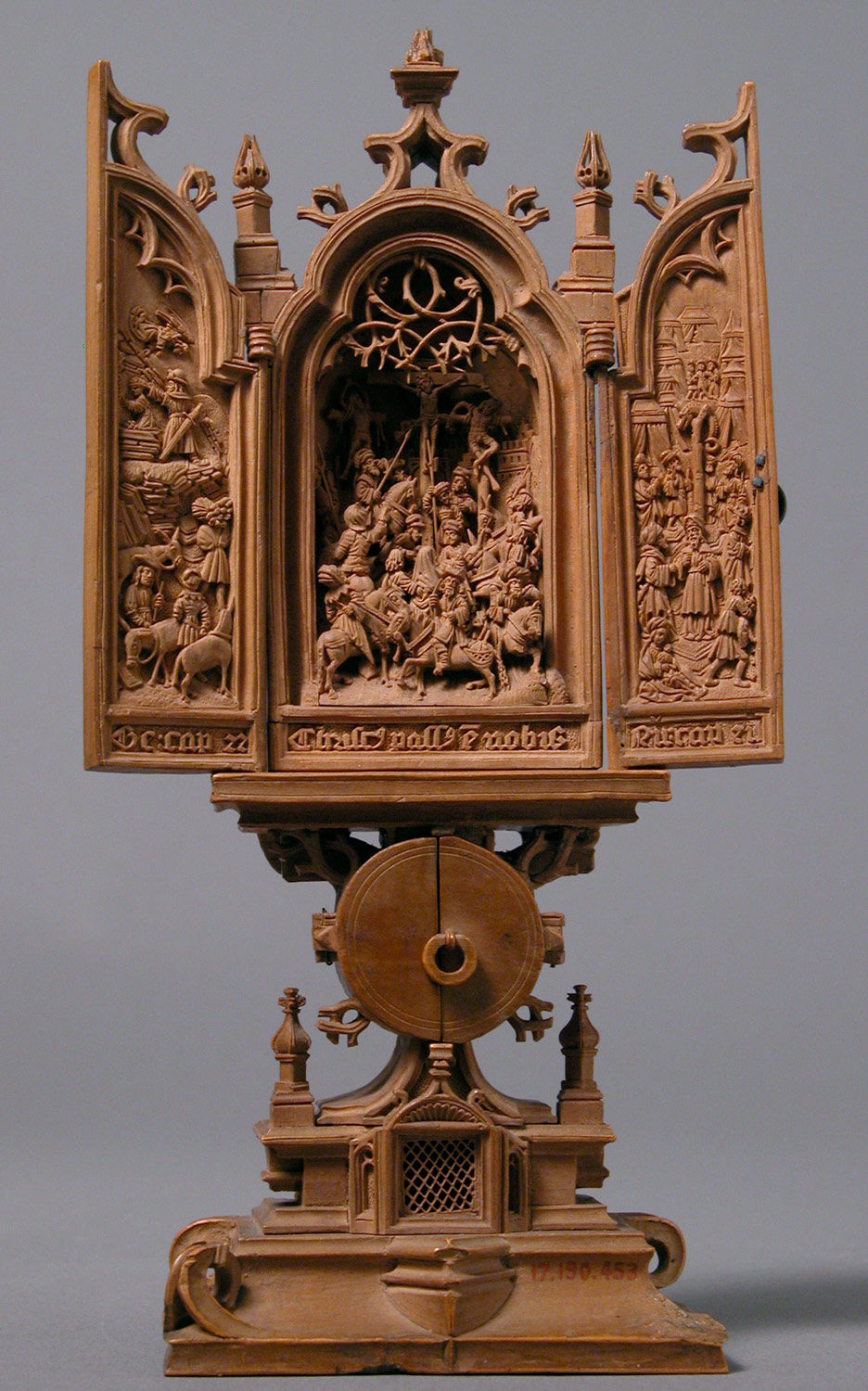

Northern triptychs and polyptychs were popular across Europe from the late 14th century, with the peak of demand lasting until the early 16th century. Preoccupied with religious subject matter, they come in two broad types: smaller, portable private devotional works, or larger altarpieces for liturgical settings. The earliest northern examples are compound works incorporating engraving and painting, usually with two painted wings that could be folded over a carved central corpus. Triptychs were commissioned by German patrons from the 1380s, with large-scale export beginning around 1400. Few of these very early examples survive, but the demand for Netherlandish altarpieces throughout Europe is evident from the many surviving examples still extant in churches across the continent.

Alongside the big church and cathedral triptychs, painted by famous artists there were also personal, small altarpieces, carved out of ivory or wood.

Secular Art

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Around the end of the 15th century, the first oil portraits of contemporary individuals, painted on small wood panels, emerged in Burgundy and France and from there quickly spread to the rest of Northern Europe. Northern European artists led the way in realistic portraits of secular subjects, and artists such as Quinten Metsys, Rogier van der Weyden, Petrus Christus, and Robert Campin produced highly detailed, realistic portraits like the ones shown here.

Secular art came into its own during the Late Gothic period with the rise of cities, foundation of universities, increase in trade, the establishment of a money-based economy and the creation of a bourgeois class who could afford to patronize the arts and commission works resulting in a proliferation of paintings and illuminated manuscripts. With the growth of cities, trade guilds were formed and artists were often required to be members of a painters' guild—as a result, because of better record keeping, more artists are known to us by name in this period than in any previous era of medieval European art.

Increased literacy and a growing body of secular vernacular literature encouraged the representation of secular themes in art. The Arnolfini marriage by van Eyck, shown in the gallery above, and Bruegel's peasant scenes already attest to this. An important outlet for secular art however were portraits of the members of the rising bourgeoisie, aristocrats and religious dignitaries, who increasingly enjoyed having their likenesses immortalized.

A wimple is a garment worn around the neck and chin, and which usually covers the head. Its use developed among women in early medieval Europe. At many stages of medieval culture it was unseemly for a married woman to show her hair. A wimple might be elaborately starched, and creased and folded in prescribed ways, even supported on wire or wicker framing (cornette).

Italian Women abandoned their head cloths in the 15th century, or replaced them with transparent gauze, and showed their elaborate braids. It took slightly longer for their Northern sisters to follow this fashion, but over time the uncovered head took hold throughout Europe.

'A Goldsmith in His Shop, Possibly Saint Eligius,' was painted in 1449 by Petrus Christus. The painting gives us a very good sense of clothing and what the interior of a shop would have looked like during the Late Gothic period.

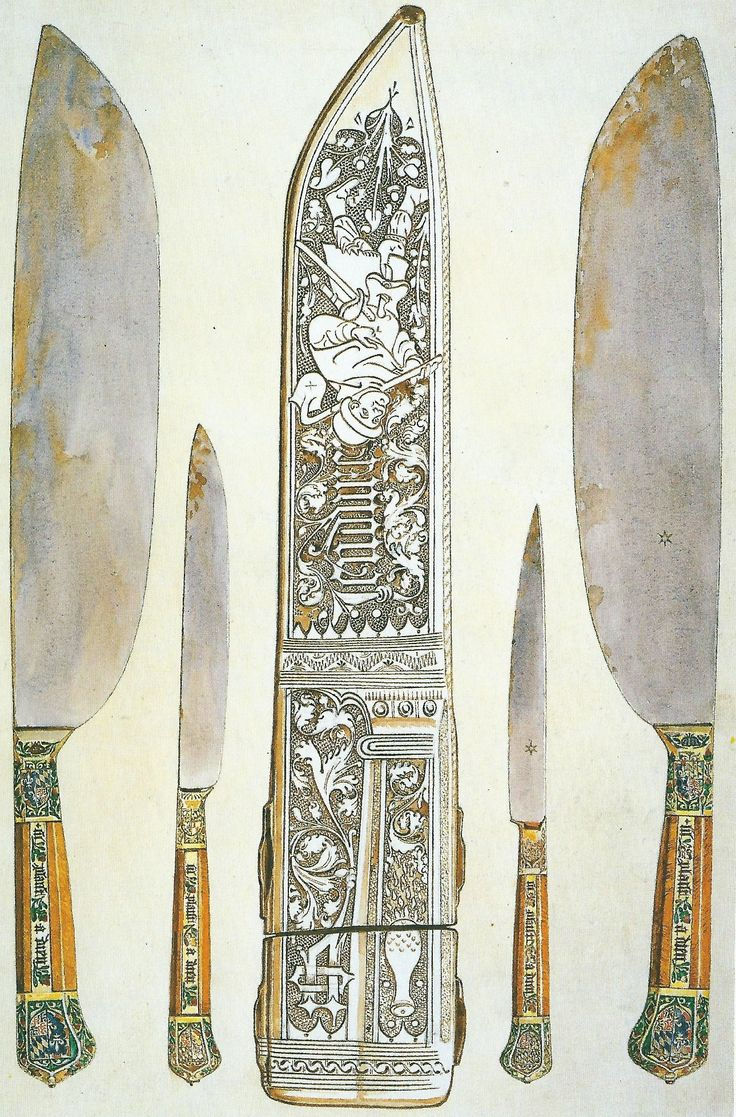

The Crafts of the Late Gothic and the Early Renaissance

In the Late Gothic period European crafts profited from a series of changes in the quality of productive knowledge and its transmission. These changes affected the formalization of craft education through apprenticeships regulated and registered by guilds, the certification of skills qualifications, novel ways of visualizing craft knowledge in print and painting, the publication of craft manuals, and finally the reproduction of such visual and textual materials in cheap printed works.

Many of these changes took place during the fifteenth century, the acceleration phase of the artisan ‘revolution.’ In almost all of these changes European crafts were distinct from their counterparts in Asia and the Near East. In themselves, none of these changes was revolutionary, but taken together they put European crafts on a trajectory of quality improvement and innovation that would in the long run create the launch-pad for the Industrial Revolution.

The furniture of the Late Gothic was usually heavy and ornamented with carved designs, primarily made of oak, since oak was easy to obtain, strong and durable. The most important piece of furniture was the chest, while the 'cup borde' was a board used to store cups. Benches and stools were used for sitting - only the rich and important ever used an actual chair. Folding chairs were popular since they could be transported when on the move.

The binaries underlying the categories of decorative, minor, applied, mechanical, functional, and even “secular” art did not exist in medieval Europe, including the Late Gothic. Goldsmiths’ and metalsmiths' work was some of the most valued. Textiles were hung on walls for both functional and aesthetic reasons, and circulated globally as diplomatic gifts. Gemstones and glass had multiple symbolic associations and metaphysical properties. Objects such as candlesticks and aquamanilia were used in the same ways in both domestic and liturgical contexts.

German Books

The Nuremberg Chronicle is an illustrated biblical paraphrase and world history that follows the story of human history related in the Bible; it includes the histories of a number of important Western cities. Written in Latin by Hartmann Schedel, with a version in German, it appeared in 1493. It is one of the best-documented early printed books—an incunabulum—and one of the first to successfully integrate illustrations and text.

After taking a look at early Netherlandish painting in order to get a sense of the lifestyle during the Late Gothic period in Europe, we now turn back to Germany which is where most of the major innovations in typography, book design and typography of the Incunabula period took place, especially through the work and influence of two individuals - Albrecht Duerer and Johannes Gutenberg.

Albrecht Duerer

We have of course already covered Albrecht Duerer's work in typography and in printmaking on the main page of the Printing Press. However, as one of the towering giants of the Northern Renaissance we will continue to take a further look at his life and times and his output in techniques and media that did not relate directly to printing.

Duerer was born in 1471 in Nuremberg. His father, Albrecht Duerer the Elder, was a successful goldsmith, who in 1455 had moved there from Hungary. Duerer's godfather was Anton Koberger, who left goldsmithing to become a printer and publisher in the year of Duerer's birth and quickly became the most successful publisher in Germany, eventually owning twenty-four printing-presses and having many offices in Germany and abroad. Koberger's most famous publication was the Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493 in German and Latin editions. It contained an unprecedented 1,809 woodcut illustrations by the Wolgemut workshop. Duerer may have worked on some of these, as the work on the project began while he was apprenticed to Wolgemut.

Self portraits in oil and tempera from 1493, 1498 and 1500.

Because Duerer left autobiographical writings and became very famous by his mid-twenties, his life is well documented by several sources. After a few years of school, Duerer started to learn the basics of goldsmithing and drawing from his father. Though his father wanted him to continue his training as a goldsmith, he showed such a precocious talent in drawing that he started as an apprentice to Michael Wolgemut at the age of fifteen in 1486. Wolgemut was the leading artist in Nuremberg at the time, with a large workshop producing a variety of works of art, in particular woodcuts for books. Nuremberg was then an important and prosperous city, a centre for publishing and many luxury trades. It had strong links with Italy, especially Venice, a relatively short distance across the Alps.

After completing his term of apprenticeship, Dürer followed the common German custom of taking gap years in which the apprentice learned skills from artists in other areas; Dürer was to spend about four years away, traveling in Northern Europe working at several workshops to extend his skills, particularly in printmaking.

Albrecht Duerer, watercolours from 1497 to 1525.

During his lifetime Duerer went to Italy twice. The first of these trips took place in 1494-1495, when he went to Venice to study its more advanced artistic world. The two visits had an enormous influence on him. His second visit to Italy occurred between 1505 and 1507, at a time when Dürer's engravings had attained great popularity and were being copied all over Europe, including Italy.

Duerer returned to Nuremberg by mid-1507, remaining in Germany until 1520. At this point his reputation had spread throughout Europe and he was on friendly terms and in communication with most of the major artists of his time, including Raphael, Giovanni Bellini and Leonardo da Vinci.

Albrecht Duerer, drawings from 1497 to 1525.

In July 1520 Dürer made his fourth and last major journey to the Netherlands. Dürer journeyed with his wife to Cologne and then to Antwerp, where he was well received and produced numerous drawings in silver-point, chalk and charcoal. He made excursions to Bruges where he saw Michelangelo's Madonna of Bruges, and to Ghent where he admired van Eyck's altarpiece.

On his return to Nuremberg, Dürer worked on a number of grand projects with religious themes, however his main focus shifted to theoretical works and he put together two major studies, the Four Books on Measurement and the Four Books on Human Proportion.

Duerer died in Nuremberg at the age of 56, leaving an estate valued at 6,874 florins - a considerable sum for his days. His large house, where his workshop was located and where his widow lived until her death in 1539, remains a prominent Nuremberg landmark which is now a museum.

Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg's (1398 - 1468) introduction of mechanical movable metal type printing to Europe started the Printing Revolution and is widely regarded as the most important invention of the second millennium, the seminal event which ushered in the modern period of human history (1439). It played a key role in the development of the Renaissance, Reformation, the Age of Enlightenment, the scientific revolution and laid the material basis for the modern knowledge-based economy and the spread of learning to the masses.

Gutenberg modified a traditional screw press that was used in agriculture to print his editions: The bed of the press held a metal matrix into which were placed movable pieces of type. Once the matrix was in place, the paper to be printed on was placed upon it and the press's weight would be used to transfer the ink on the surface of the type pieces to the paper.

Gutenberg's method for making type is considered to have included a metal alloy and a hand mold for casting type. The alloy was a mixture of lead, tin, and antimony that melted at a relatively low temperature for faster and more economical casting while also creating a durable type.

Among Gutenberg's many contributions to printing are: the invention of a process for mass-producing movable type; the use of oil-based ink for printing books; adjustable molds;and the use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses of the period. His truly epochal invention was the combination of these elements into a practical system that allowed the mass production of printed books and was economically viable for printers and readers alike. The use of movable type was a marked improvement on the handwritten manuscript or the Incunabula books made with wood-printing techniques, which were the existing methods of book production in Europe, thus revolutionizing European book-making.

In Renaissance Europe, the arrival of mechanical movable type printing introduced the era of mass communication which permanently altered the structure of society. The relatively unrestricted circulation of information - including revolutionary ideas - transcended borders, captured the masses in the Reformation and threatened the power of political and religious authorities. The increase in literacy broke the monopoly of the religious and aristocratic elite on learning and bolstered the emerging middle class. Across Europe, the increasing cultural self-awareness of its people led to the rise of proto-nationalism, accelerated by the flowering of the European vernacular languages to the detriment of Latin's status as lingua franca. In the 19th century, the replacement of the hand-operated Gutenberg-style press by steam-powered rotary presses allowed printing on an industrial scale, while Western-style printing was adopted all over the world, becoming practically the sole medium for modern bulk printing.