The History

of Visual

Communication

Between Two Wars

World War 1

World War 1 was an international conflict that in 1914–18 embroiled most of the nations of Europe along with Russia, the United States, the Middle East, and other regions. The war pitted the Central Powers—mainly Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey—against the Allies—mainly France, Great Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan, and, from 1917, the United States. It ended with the defeat of the Central Powers. The war was virtually unprecedented in the slaughter, carnage, and destruction it caused.

vvv

The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I was about 40 million: estimates range from around 15 to 22 million deaths[1] and about 23 million wounded military personnel, ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history. The total number of deaths includes from 9 to 11 million military personnel. The civilian death toll was about 6 to 13 million.

vvv

World War I was one of the great watersheds of 20th-century geopolitical history. It led to the fall of four great imperial dynasties (in Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey), resulted in the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, and, in its destabilization of European society, laid the groundwork for World War II.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |

World War 1 was an ugly, merciless war that (among other types of battlefields) was especially fought in trenches.

Trench Warfare

World War I was a war of trenches.

After the early war of movement in the late summer of 1914, artillery and machine guns forced the armies on the Western Front to dig trenches to protect themselves. Over the next four years, both sides would launch attacks against the enemy’s trench lines, attacks that resulted in horrific casualties.

Inside a trench, all that is visible is just a few feet on either side, ending at the trench walls in front and back, with a patch of leaden sky visible above. Trenches in WWI were constructed with sandbags, wooden planks, woven sticks, tangled barbed wire or even just stinking mud. Despite the use of wooden plank ‘duckboards’ and sandbags to keep out the water, soldiers on the front lines lived mired in mud. “The mud in Belgium varies in consistency from water to about the thickness of dough ready for the oven,” one British infantry soldier wrote. The constant damp often led to a condition known as ‘trenchfoot,’ which if left untreated, could require amputation to stave off severe infection or even death.

Trenches became trash dumps of the detritus of war: broken ammunition boxes, empty cartridges, torn uniforms, shattered helmets, soiled bandages, shrapnel balls, bone fragments. Trenches were also places of despair, becoming long graves when they collapsed from the weight of the war.

‘No-man’s land,’ was an ancient term that gained terrible new meanings during WWI. The constant bombardment of modern artillery and rapid firing of machine guns created a nightmarish wasteland between the enemies’ lines, littered with tree stumps and snarls of barbed wire. In battle, soldiers had to charge out of the trenches and across no-man’s land into a hail of bullets and shrapnel and poison gas. They were easy targets and casualties were enormously high. By the end of 1914, after just five months of fighting, the number of dead and wounded exceeded four million men.

The Aftermath

The aftermath of World War I saw cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, new ones were formed, boundaries were redrawn, international organizations were established, and many new and old ideologies took a firm hold in people's minds.

World War I also had the effect of bringing political transformation to most of the principal parties involved in the conflict, transforming them into electoral democracies by bringing near-universal suffrage for the first time in history, as in Germany (1919 German federal election), Great Britain (1918 United Kingdom general election), and Turkey (1923 Turkish Republic general election).

In the United States, at the end of the war, 20 percent of American men aged eighteen to forty-five were in the military. Demobilization was chaotic, with no real national plan to suddenly reintegrate about 4,000,000 military personnel back into civilian society and an economy thrust into recession. Migration to war production centers and high wages due to labor scarcity had dramatically raised the cost of living as increased labor strength and militancy combined with deferred wartime grievances and the dismantling of federal arbitration to turn 1919 into a record strike year. Political and economic elites feared that the combat-hardened men of the Meuse-Argonne offensive would turn toward unions, or even to revolution. Black veterans saw their hopes frustrated as their service was rewarded not with more equal citizenship and opportunity, but with a wave of violence against their communities.

Cultural Despair

The destruction and catastrophic loss of life during World War I led to what can best be described as a cultural despair in many former combatant nations. Disillusionment with international and national politics and a sense of distrust in political leaders and government officials spread throughout the consciousness of a public which had witnessed the ravages of a devastating four-year conflict. Most European countries had lost virtually a generation of their young men.

vvv

While some writers like German author Ernst Jünger glorified the violence of war and the conflict's national context in his 1920 work Storm of Steel (Stahlgewittern), it was the vivid and realistic account of trench warfare portrayed in Erich Maria Remarque's 1929 masterpiece All Quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen nichts Neues) which captured the experience of frontline troops and expressed the alienation of the "lost generation" who returned from war and found themselves unable to adapt to peacetime and tragically misunderstood by a home front population who had not seen the horrors of war firsthand.

vvv

In some circles this detachment and disillusionment with politics and conflict fostered an increase in pacifist sentiment. In the United States public opinion favored a return to isolationism; such popular sentiment was at the root of the US Senate's refusal to ratify the Versailles Treaty and approve US membership in President Wilson's own proposed League of Nations. For a generation of Germans, this social alienation and political disillusionment was captured in German author Hans Fallada's Little Man, What Now? (Kleiner Mann, was nun?), the story of a German "everyman," caught up in the turmoil of economic crisis and unemployment, and equally vulnerable to the calls of the radical political Left and Right. Fallada's 1932 novel accurately portrayed the Germany of his time: a country immersed in economic and social unrest and polarized at the opposite ends of its political spectrum.

The Roaring '20s

The changes in society were immense throught the Western World and beyond, including the Middle East. The fall of monarchies and the rise of dictatorships. The spread of extremist and radical ideologies like Communism, Fascism and eventually Nazism. Social Darwinism and Nihilism also become more popular social trends. After WW1, half of Europe was in shambles whether actually like Northern France and Belgium, or economically and/or politically. The entire fabric of society in many areas became ripped up and created an environment that would eventually lead to another world war only around two decades later.

While society in many areas became undone, culture still flourished throughout the Western World after WW1. Jazz spread in popularity through many parts of the Western World, not just in the U.S. Art Deco, Surrealism, and Expressionism all took hold of the art world right before, during and after WW1. Cabaret dancing became more popular in many major European cities like Berlin, Paris and London. Literature tended to lean to more realism and less romanticism. This makes sense when a good amount of artists and writers in Europe had been affected by the death and destruction of the war in some way. Most of them weren’t looking to write happy fairy tales or paint romanized views of the world.

World War 1 undoubted laid the foundations for the modern world we live in today.

|  |  |  |  |

|---|

The period from the end of the First World War until the start of the Depression in 1929 is known as the "Jazz Age", fueled by the prohibition of alcohol and the subsequent rise of the "speakeasies". Jazz had become popular music first in America rapidly spreading to the rest of the globe, although older generations considered the music immoral and threatening to cultural values. Dances such as the Charleston and the Black Bottom were very popular during the period, and jazz bands typically consisted of seven to twelve musicians. Important orchestras in New York were led by Fletcher Henderson, Paul Whiteman and Duke Ellington.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|

The Car: This extravagance was ignited by the introduction of Henry Ford's Model T, a car affectionately known as the "Tin Lizzie." Cars became a major source of freedom and adventure as well as travel, and cars greatly altered the standard of living, the social patterns of the day, and urban planning; and cars differentiated suburban and urban living purposes. In addition, the rise of cars led to the creation of new leisure activities and businesses. The car became the center of middle and working class life until the start of World War II.

The Radio: Listening to the newly invented radio became increasingly popular during this period, which further encouraged the desires of people for Hollywood style lives of indulgence and ease. Radio had many possibilities. The ability to get news and information to people quickly created several new types of programs on the radio such as headlines, remote reporting, panel discussions, weather reports, and farm reports. In addition to news and music, radio also attracted top comedy talents from vaudeville and Hollywood as well as radio dramas ans sitcoms.

The Flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee height was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered acceptable behavior. Flappers were seen as brash for wearing excessive makeup, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes in public, driving automobiles, treating sex in a casual manner, and otherwise flouting social and sexual norms. As automobiles became more available, flappers gained freedom of movement and privacy.

Flappers are icons of the Roaring Twenties, a period of postwar social and political turbulence and increased transatlantic cultural exchange, as well as of the export of American jazz culture to Europe. More conservative people, who belonged mostly to older generations, reacted with claims that the flappers' dresses were "near nakedness" and that flappers were "flippant", "reckless", and unintelligent.

While initially associated with the United States, this "modern girl" archetype was a worldwide phenomenon that had other names depending on the country, such as joven moderna in Argentina or garçonne in France, although the American term "flapper" was the most widespread internationally.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

A major cause of the change in young women's behavior was World War I, which ended in November 1918. The death of large numbers of young men in the war, inspired in young people a feeling that life is short and could end at any moment. Therefore, young women wanted to spend their youth enjoying their life and freedom rather than just staying at home and waiting for a man to marry them.

Political changes were another cause of the flapper culture. World War I reduced the grip of the class system on both sides of the Atlantic, encouraging different classes to mingle and share their sense of freedom. Women finally won the right to vote in the United States on August 26, 1920. Women wanted to be men's social equals and were faced with the difficult realization of the larger goals of feminism: individuality, full political participation, economic independence, and 'sex rights'.

Although women had become more involved in ‘white-collar’ jobs by the turn of the century, the "Great War" is often seen as a major turning point in the role of women in Western societies. During the war the biggest increase in female employment was in factories, particularly in munitions. Once the war ended women refused to relinquish the independence that came with the newly found sense of identity that placed them inside the workplace alongside men.

As part of this big social change flappers were considered a significant challenge to traditional Victorian gender roles, devotion to plain-living, hard work and religion. Increasingly, women discarded old, rigid ideas about roles and embraced consumerism and personal choice, and were often described in terms of representing a "culture war" of old versus new. Flappers also advocated voting rights which were eventually passed into law across many countries over the coming decade.

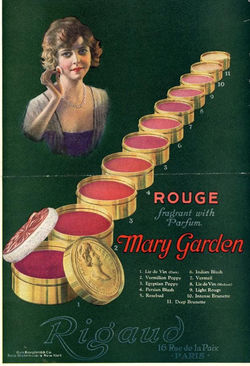

Advertising

During the 1920s, sophisticated salespeople, graphic designers, and copywriters bombarded Western populations with attractive, persuasive advertising campaigns. Modern advertising sought to convince consumers that the key to increased status, health, happiness, wealth, and beauty existed in the mass-produced goods available in department stores, chain stores, and mail-order catalogs. In prior decades, people had tended to define themselves on factors such as race, ethnicity, region, religion, and politics. During the 1920s, however, they increasingly defined themselves through the houses, cars, clothes, and other goods and services they purchased.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |

Edward Bernays

At the time of his death in 1939, Sigmund Freud’s ideas on psychoanalysis were already creating waves in the US, thanks to his nephew Edward Bernays. The First World War had increased consumption in the society and a number of factories had sprung up to meet that demand. With the war over, these factories started churning out mass-produced consumer products. But their marketing strategy involved only harping on the product’s features. Even luxury products like automobiles were marketed focusing only on functional benefits derived from the product.

Using Freud’s ideas on psychoanalysis (without the consent of his uncle who actually temporarily disowned him due to this usage), Bernays showed American corporations how to sell a product (or service) to a consumer’s emotions rather than his intellect. He started to play the central role in a concerted effort by American corporations to transform America from a “need-based” to a “desire-based” society in order to increase goods consumption. Bernays did this by linking products to the irrational forces in the human subconscious which were unearthed by his uncle. At a time when cigarette consumption by women was considered a taboo, he portrayed cigarettes as “Torches of freedom” linking them to women empowerment- a challenge to male authority, thereby greatly increasing sales. He not only increased cigarette sales by opening up a market, hitherto untouched (almost), but brought about a paradigm shift in the society- the idea that smoking cigarettes makes a woman more independent exists to this day in the American society. He was also instrumental in increasing public participation in the incipient American stock markets and took celebrity endorsements of products to new heights. He was the first to use promotional techniques like product placement in movies and movie premieres.

Cultural Icons

Although there have been cultural icons throughout the ages, with the onset of art and entertainment forms that were based upon mass communication platforms such as the radio and the movies, cultural icons acquired very special prominence in post World War 1 societies.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |

|

They mostly came from the cinema, from the music and stage industries but also from the worlds of sports, fashion and even aviation.

Intellectual Icons

But it wasn't only performers and such, many intellectuals of the day also found wide coverage - from Albert Einstein to Scott Fitzgerald, the public also followed writers, scientists and artists.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression (1929–1939) was an economic shock that affected most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagion began around September 1929 and led to the Wall Street stock market crash of October 24 (Black Thursday). It was the longest, deepest, and most widespread depression of the 20th century. Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide gross domestic product (GDP) fell by an estimated 15%. Devastating effects were seen in both rich and poor countries with falling personal income, prices, tax revenues, and profits. International trade fell by more than 50%, unemployment in the U.S. rose to 23% and in some countries rose as high as 33%.

"Migrant Mother" is a photograph of Florence Owens Thompson taken in 1936 in Nipomo, California by American photographer Dorothea Lange.

Cities around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries. Farming communities and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell by about 60%. Faced with plummeting demand and few job alternatives, areas dependent on primary sector industries suffered the most.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|

The common view among economic historians is that the Great Depression ended with the advent of World War II. Many economists believe that government spending on the war caused or at least accelerated recovery from the Great Depression with the rearmament policies leading up to World War II helped stimulate the economies of Europe in 1937–1939.

Escapism

Escapist culture during the Great Depression is rooted in popular culture, mass production, mass distribution, and mass consumption experienced by an increasing percentage of people all over the globe. Especially across the Western world populations were continuing to become more and more urbanized, which saw to it that the spread of popular cultural forms with their emphasis on humor, melodrama, craziness was easily achieved.

Thus the depression years were ones in which popular culture was sustained, and in many cases thrived. This was probably possible, in part, because of people's desire to escape from the stress associated with economic instability coupled with technological developments commercialized for entertainment purposes.

Entrepreneurs, investors, and popular culture promoters exploited the public's desperate desire to escape by continually creating, distributing and promoting radio shows, movies, print media, fads, sporting events and the like for an eager audience. This creativity was simultaneously stimulated by technological developments, which allowed for the mass distribution and consumption of what was being created. Hearing a piece of favorite music by a particular orchestra was no longer dependent upon being near a concert or dance hall. Technological advances allowed music to be available coast to coast over network radio. The same was also true of sporting events. Technology associated with the motion picture allowed the nation to sit together in movie theaters across the country and enjoy the common experience of watching their favorite actors play compelling roles in fascinating stories.

The Movies

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |

|

The 1930s are also referred to as the "Golden Age" of movie making because of the quantity, quality, and breadth of the films being made, as well as the quality of the actors appearing in them. Twenty-two movies, either released or in production from this period, are on the American Film Institute's (AFI) list of the one hundred greatest films produced between 1915 and 2000. At least 34 of the stars listed among the 50 greatest screen legends appeared in films during the 1930s. No other decade is as well represented.

The popularity of films during the Great Depression is usually associated with people desiring an escape from the economic brutality of everyday life. In support of this belief is the fact that very few films from the period deal with the Great Depression in a realistic way. One notable exception is the Grapes of Wrath (1940), directed by John Ford and starring Henry Fonda. More typical for the period were movies associated with genres such as gangster, comedy, animated features, musicals, westerns, horror, melodramas, costume dramas, thrillers, and literary dramas.

Cartoons

The golden age of American animation was a period in the history of U.S. animation that began with the popularization of sound cartoons in 1928 and gradually ended in the final quarter of the 20th century. The most notable of the genre was Walt Disney with his creation Micky Mouse whose close competitor was Bill Nolan who is credited with inventing the rubber hose approach, who gave rounded flexibility to his animation in the silent Felix the Cat and Krazy Kat shorts.

The world of these cartoons is infectiously charming. Characters are constantly bobbing up and down to the beat and any prop or body part can be turned into a musical instrument at a moment’s notice and aren’t hindered by dull concepts like realism and internal consistency. Inanimate objects frequently come alive and get involved in the action, as seen in the Max Fleischer short Barnacle Bill (1930), starring Bimbo. Characters can also detach their limbs or heads for the sake of a sight gag, as demonstrated by Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in Broadway Folly (1930).

Please go to this page to see many clips of 1930 toons:

https://www.cartoonbrew.com/cartoon-study/the-rubber-hose-classics-that-inspired-the-cuphead-show-213700.html

Comics

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

Comic strips first began appearing in newspapers towards the close of the nineteenth century. During the Depression, strips and comic books began to feature characters very much like those found in the pulps. Readers could enjoy the capers of "Dick Tracy," the jungle adventures of "Tarzan," the heroics of "Prince Valiant," the domestic comedy of "Blondie," and the super heroics of "Superman," "Batman," and "Wonder Woman." Expertly drawn, with great attention paid to rendering the human figure in action, these strips and books captivated both children and adults with action oriented adventures. Good always triumphed over evil, but not without the heroes or characters being first put to the test and facing down certain death or domestic chaos. Comic strips and books were both criticized regularly for their violence, slapstick, and political leanings. For example, Daddy Warbucks in the comic strip "Little Orphan Annie" was regularly singled out for representing corporate greed.

The post WW1 period that led into the Roaring '20s and from there into the years of the Great Depression both overlaps and blends seamlessly into the early to mid 20th century period of Modernism in architecture and design which is the subject matter of the next chapter in this history of visual communication.